|

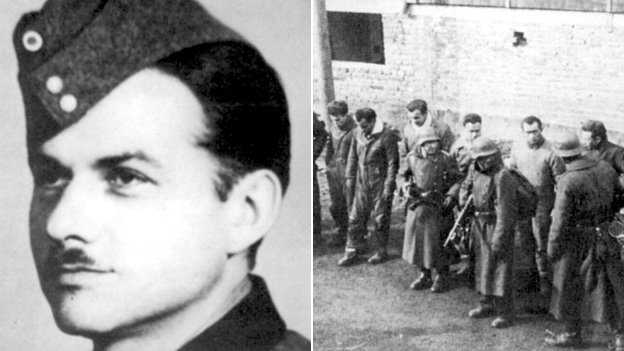

Published: October 15, 2012 Much of the debate about the interrogation of suspected terrorists has been about whether the methods used, such as waterboarding, could be described as torture. Historian Julian Putkowski examines how a German Luftwaffe interrogator used persuasion rather than punishment to get prisoners of war to talk. During the latter part of World War II lots of allied fliers got shot down over Germany. Many of the survivors - or terrorfliegers as they were termed by the Nazis - got rounded up and were dispatched to Luftwaffe's interrogation unit at Dulag Luft POW Camp, near Oberursel. After being marched into the camp, they were placed in solitary confinement and in spite of the provisions of the Geneva Convention, they anticipated rough handling, possibly having their fingernails torn off by Nazi torturers. Aircrew who anticipated a Gestapo-style battering were in for a surprise when they encountered Obergefreiter Hanns Scharff, who had acquired fluent English when working as a businessman in pre-war South Africa. Although his inscrutability secured him the nick-name Stone Face, he was otherwise a genial fellow. He was a self-taught interrogator who used persuasion rather than punishment as a strategy for getting Allied prisoners of war to disclose more than the customary name, rank and number, permitted by the Geneva Convention. Scharff always began by doing his homework thoroughly. Before commencing an interrogation session, he checked all available data, generally acquainting himself with whatever was known about the pilot's service and personal circumstances. Zoo tripsThe Scharff method, if so it may be called, relied on the initial premise that it was better for a flier to co-operate with the Luftwaffe, instead of being regarded as a spy and handed over to the Gestapo. Even though there were a few prisoners who remained button-lipped, Scharff resolutely refused to descend to using physical coercion. Instead of using pliers to squeeze information out of prisoners, Scharff got what he and his superiors wanted by playing on a prisoner's sense of isolation and psychological insecurity. Carefully deploying what were sometimes meagre scraps of data, Scharff sought to create the illusion of total knowledge about a prisoner's activities. Misled into believing that the interrogator knew just about everything anyway, the latter could then be bamboozled into disclosing military secrets. Scharff appeared to reverse the overtly adversarial relationship between interrogator and prisoner by adopting a subtle, softly-softly approach. He pretended to be a prisoner's best pal. Masquerading as a nice guy, Scharff arranged for special treats outside the confines of Dulag Luft. He arranged for one prisoner to enjoy a brief flight in a German fighter plane, prisoners were treated to slap-up feeds with German fliers, granted medical treatment and even permitted to go on an outing to the local zoo. Typically, after extracting a precautionary undertaking that he would not use the opportunity to make a bid to escape, a prisoner could enjoy a visit to Oberursel forest, with Scharff acting as chaperone and guide. Rambling along woodland paths the two men chatted about the flora and fauna and engaged in small talk, including for example, musing about British and US social activities or customs. Interrogator's guest bookThe prisoners never generally recalled discussing anything of any military significance but all the time Scharff was actually conducting a casual but systematic interrogation, harvesting useful intelligence information.

Prisoners unwittingly divulged details about training regimes, operational plans and data about guns, bomb sights, aircraft capability, tactical manoeuvres, call signs, wireless frequencies and communications. Before departing for internment in other POW camps, they cheerfully signed their interrogator's guest book. They expressed appreciation about the professional but hospitable manner in which they felt they had been treated. As for Scharff, he subsequently claimed that by befriending a POW he could obtain information from 90% of all prisoners. It was a bold claim but Scharff was a good interrogator - he was very, very good. After the war ended he was summoned to the USA, initially to testify to a Grand Jury in a treason trial that involved US citizens suspected of wartime collaboration with the Nazis. He settled down in New York and began to develop a business designing and marketing decorative mosaics but could not escape the past. During the early 1950's he was feted in newspaper and magazine articles as the "master interrogator". His former enemies became his friends and wartime POWs welcomed him at their reunions. Some of the less-well publicised aspects of Scharff's post-war activities involved him being de-briefed by the US Air Force and lecturing intelligence and security agencies about non-coercive interrogation techniques. Much of what he had to relate reflected Scharff's firm conviction that interrogation could succeed without treating prisoners in an inhumane manner. Scharff died in California 20 years ago but his legacy remains. At first his name did not figure in the sharp and bitter public exchanges about the morality of waterboarding and so-called "enhanced interrogation techniques" that were sanctioned by President George Bush and inflicted on alleged terrorists detained in Abu Ghraib prison, Guantanamo Bay and secret CIA detention centre. However, nowadays top US interrogators, including Ali Soufan, who are critical about the efficacy of enhanced interrogation being used in today's "war on terror", have revived public interest in Scharff's successful interrogation of Allied "terrorfliegers" during World War II. http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/0/19923902 Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed