|

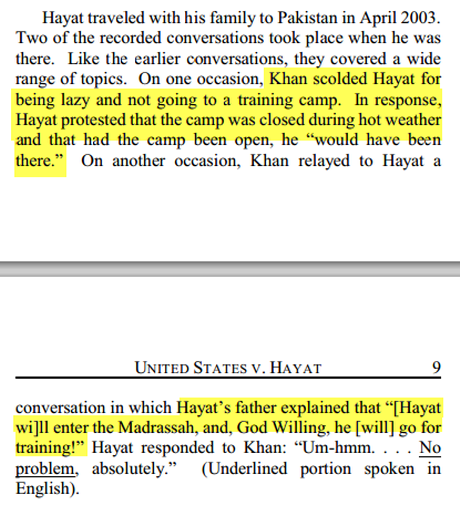

A court ruling in one of the most abusive prosecutions yet highlights the dangers posed by this familiar tactic Glenn Greenwald guardian.co.uk, Tuesday 19 March 2013 12.10 EDT One of the major governmental abuses denounced by the 1976 final report of the Church Committee was the FBI's domestic counter intelligence programs (COINTELPRO). Under that program, the FBI targeted political groups and individuals it deemed subversive and dangerous - including civil rights activists (such as the NAACP and Martin Luther King), black nationalist movements, socialist and communist organizations, anti-war protesters, and various right-wing groups - and infiltrated them with agents who, among other things, attempted to manipulate members into agreeing to commit criminal acts so that the FBI could arrest and prosecute them. This program was exposed only because a left-wing group, the so-called "Citizens' Commission to Investigate the FBI", broke into an FBI office in Pennsylvania, stole the files relating to the program, and sent them to various newspapers. What made the program so controversial was that the FBI was attempting to create and encourage crimes rather than find actual criminals - all in order to punish those whose constitutionally protected political activism the US government found threatening. As Noam Chomsky wrote in a comprehensive 1999 article on the program: "During these years, FBI provocateurs repeatedly urged and initiated violent acts, including forceful disruption of meetings and demonstrations on and off university campuses, attacks on police, bombings, and so on." Once the program was exposed, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover insisted that there was no centralized authority for it and that it had ended, while the Church Committee's final report made clear just how illegal and threatening it was: "Nearly every major post-9/11 terrorism-related prosecution has involved a sting operation, at the center of which is a government informant. In these cases, the informants — who work for money or are seeking leniency on criminal charges of their own — have crossed the line from merely observing potential criminal behavior to encouraging and assisting people to participate in plots that are largely scripted by the FBI itself. Under the FBI's guiding hand, the informants provide the weapons, suggest the targets and even initiate the inflammatory political rhetoric that later elevates the charges to the level of terrorism." Like most abusive post-9/11 trends, this tactic is now stronger than never: "there have been 138 terrorism or national security prosecutions involving informants since 2001, and more than a third of those have occurred in the past three years." As common as this tactic has become, it's vital to look at particularly egregious cases to see what is really at play. This week, a panel of the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals, by a 2-1 decision, affirmed the 2005 "material support" conviction of US-born Hamid Hayat, and it's one of the worst yet most illustrative cases yet (that's US justice: he was convicted 8 years ago, and his appeal is only now decided). Hayat was convicted for allegedly having attended "a terrorist training camp" when he was 19 years old. Writing this week in the Sacramento Bee, Stanford Law Professor Shirin Sinnar wrote: "Even among anticipatory prosecutions, this case stands out for the fragility of the government's case and the rank taint of prejudice, raising the haunting prospect that a man who had done nothing was convicted for a violent state of mind." Notably, the dissenting judge was A. Wallace Tashima, the first Japanese-American appointed to the federal bench; he was imprisoned during World War II in an internment camp in Arizona. As Professor Sinnar observed: "Perhaps as a Japanese American who was interned as a child, he remembered well the danger of preventative security measures founded on group-based judgments." In dissent, Judge Tashima wrote: "This case is a stark demonstration of the unsettling and untoward consequences of the government's use of anticipatory prosecution as a weapon in the 'war on terrorism.'" He then described anticipatory prosecutions and explained why they are so dangerous: The evidence that Hayat attended a "terrorist training camp" came from a government informant, Nassem Kahn, who was originally arrested by the FBI as part of money laundering scheme. But rather then prosecute Kahn, he was paid between $3,000 and $4,000 per month - as the dissent said, "more than $200,000 by the FBI" total - to infiltrate a local mosque in Lodi, California. That is how he befriended the then-19-year-old Hayat and began trying to induce him into criminal conduct. Desperate to maintain his payments, Kahn outright fabricated stories in order to show his value, including claims - which even the FBI acknowledged were false - that he had on several occsaions seen al-Qaida's then-second-highest official, Ayman al Zawahiri, at the Lodi mosque. Over the course of hundreds of hours of recorded conversations, Kahn actively encouraged Hayat to attend a terrorist camp in Pakistan. At one point, he even mocked the youth for failing to do so, and on another, told Hayat that he had spoken to Hayat's father who wanted him to go to the camp: Remarkably, the judge allowed Kahn to testify that Hayat told him that he attended a camp, but then refused to allow Hayat's lawyers to ask Kahn about the fact that Hayat eventually told him that he never intended to go to a camp and was simply lying out of bravado. That is one major factor that caused Judge Tashima to insist that the conviction must be reversed: "The prosecution was allowed to introduce inculpatory out-of-court statements Hayat made to Khan, but the defense was prevented from eliciting testimony regarding Hayat's exculpatory out-of-court statements made in the same conversation. . . . . The district court's exclusion of a crucial exculpatory statement made under identical conditions and contemporaneously with the inculpatory statement was grossly unfair. . . . This seriously calls into question the fairness and integrity of the proceedings." Worse, the prosecution was allowed to introduce "expert testimony" telling the jury that "a particular kind of person would carry" a "supplication" prayer written in Arabic that was found in Hayat's wallet: namely, "a person who perceives him or herself as being engaged in war for God against an enemy". As bad as it was to allow such blanket "expert testimony" about his likely state of mind based on a prayer in his wallet, the judge then excluded Hayat's own expert witness who would have testified that such a prayer is common among perfectly peaceful Muslims and has all sorts of possible meanings. As Judge Tashima pointed out, Hayat was merely carrying "a written prayer, whose meaning to any particular faithful likely is obscure. This is particularly so in this case because Hayat did not speak or read Arabic, the language in which the prayer was written." To decide that someone is a Terrorist deserving of decades in prison because of that is a travesty beyond belief. The only other evidence presented was a videotape in which Hayat, after many hours of being badgered in FBI custody, finally said that he had been present a camp at which terrorists were "possibly" or "probably" present. But even an FBI agent, citing how vague and coerced the statement was, himself deemed it the "sorriest confession [he had] ever seen." Judge Tashima derided it as "a meandering and almost nonsensical confession to the FBI". He added that the "confession" was extracted only "after hours of questioning, beginning around 11:00 a.m., and lasting into the early morning hours of the following day, [when] he finally agreed with FBI interrogators, who repeatedly insisted, despite his continuing denials, that Hayat had in fact attended such a training camp." The trial judge refused to allow expert testimony about how and why it was clear that this statement had been coerced. But worst of all - and most revealing - the jury foreperson, Joseph Cote, made all sorts of post-trial statements demonstrating clear Islamophobic bias. Cote excused the FBI informant's fabrications that he had seen al-Zawhiri at the Lodi moseque by saying: "they all look the same when wearing a costume". Other jurors swore in affidavits that "[t]hroughout the deliberation process, Mr. Cote made other inappropriate racial comments." In an interview with the Atlantic, Cote, noting the 2005 London subway bombings, said that he could not let Hayat go free "on the basis of what we know of how people of his background have acted in the past." That is as bigoted a statement as it gets: that Hayat should be subjected to heightened suspicion because he is Muslim. That's exactly the mindset that has led the US to create what New York Times editorial page editor Andy Rosenthal has called "essentially a separate justice system for Muslims." Indeed, Cote specifically endorsed the government's post-9/11 tactic of preemptively prosecuting Muslims. As the Atlantic article by Amy Waldman explained, the US government's treatment of Muslims is a direct repudiation of what had long been the core precept of US justice: "Testifying before Congress in 2004, Paul Rosenzweig of the Heritage Foundation paraphrased a well-known maxim, saying, 'It is better that ten guilty go free than that one innocent be mistakenly punished.' September 11 changed the paradigm, he argued, and now, 'we simply cannot afford a rule that 'Better ten terrorists go undetected than that the conduct of one innocent be mistakenly examined.'" The Atlantic article then quoted Cote, again citing the danger from Muslims, as wholeheartedly concurring with this mindset: "This preventive approach, Cote said, means that 'just as there are people in prison who never committed the crime, this may also happen . . . .He argued that it was 'absolutely' better to run the risk of convicting an innocent man than to let a guilty one go. 'Too many lives are changed' by terrorism, he said. 'So shall one man pay to save fifty? It's not a debatable question." Despite all these comments, the two judges voting to affirm Hayat's conviction contorted themselves into pretzels to find non-bigoted interpretations of these comments and to conclude, ultimately, that even if ugly, these sentiments are not enough to compel a new trial. After the jury found him guilty, Hayat was sentenced to 288 months - 24 years - in federal prison. That included the maximum 15-year sentence for "materially supporting" terrorism. Convicted at the age of 23 and now 30 years old, Hayat will not be free until he's 47 years old - even though there was zero evidence that he had taken any steps to harm anyone. That's why I say that this case, though extreme, is incredibly illustrative. It's how these cases against young Muslims - and, increasingly, non-Muslim activists in the US - typically function. The FBI, using a paid informant, spent years trying to turn him into a criminal. Even with all those efforts, they obtained virtually nothing, but were able to play on the anti-Muslim prejudices of American jurors who equate Muslim religiosity with evidence of Terrorism. But what makes the case so pernicious, what makes the tactic so dangerous, is exactly what the Church Committee cited when denouncing COINTELPRO: namely, it is the US government targeting citizens for their political beliefs, and then turning them into criminals by exploiting their unpopular political views. Here is the summary of the "evidence" against Hayat from the Atlantic's Waldman: "To prove intent, then, the government had to turn to the rubble of Hayat's life—an accretion of circumstantial but ugly evidence that prosecutors said proved 'a jihadi heart and a jihadi mind.' There were Hayat's words, taped by an informant, in which he praised the murder and mutilation of the journalist Daniel Pearl: 'They killed him—I'm so pleased about that. They cut him into pieces and sent him back … That was a good job they did—now they can't send one Jewish person to Pakistan.' There was what the prosecution called Hayat's 'frequently expressed hatred toward the United States'; his comment that his heart 'belongs to Pakistan'; his description of President Bush as 'the worm.' There was, at his house, literature by a virulent Pakistani militant and a scrapbook of clippings celebrating both the Taliban and sectarian violence." It's incredibly common for young people of that age to dabble in extremist thought. But whatever one thinks of those opinions, they are clearly constitutionally protected as free speech. Yet throwing these opinions in the face of the jury, combined with evidence of one's belief in Islam, is more than enough to persuade all too many Americans that the person is guilty of Terrorism, that he has "a jihadi heart and a jihadi mind". And that's what makes these "preemptive" and "anticipatory" prosecutions so menacing: by criminalizing free speech and turning dissidents into felons, they achieve exactly that which the First Amendment, above all else, was designed to prohibit. That these practices created such an intense backlash when exposed 40 years ago by the Church Committee, yet are accepted with such indifference now, speaks volumes about the state of US political culture.

http://www.guardian.co.uk/commentisfree/2013/mar/19/preemptive-prosecution-muslims-cointelpro Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed