|

Fifteen years ago, Lemony Snicket's A Series of Unfortunate Events built a huge following among children–in part because it used highly self-conscious, experimental literary techniques. LENIKA CRUZ With a plot featuring accidental dismemberment, death by leeches, serial arsonists, and rampant child abuse, A Series of Unfortunate Events seemed to descend from the Grimm's Fairy Tales tradition of juvenile fiction. The tragicomic 13-book series, which debuted 15 years ago, chronicled the plight of the three Baudelaire orphans, whose lives become a hamster wheel of misery after their parents die in a mysterious fire. The books sold more than 60 million copies internationally, spawning a video game, fan sites, companion books, and a 2004 film adaptation starring Jim Carrey. A year after the series began, I received a copy of the first, alliteratively titled novel The Bad Beginning as a Christmas gift. I fell in love—partly because of the absurdist storyline and the likable but unlucky young trio: Violet the inventor, Klaus the reader, and Sunny the baby with sharp teeth.

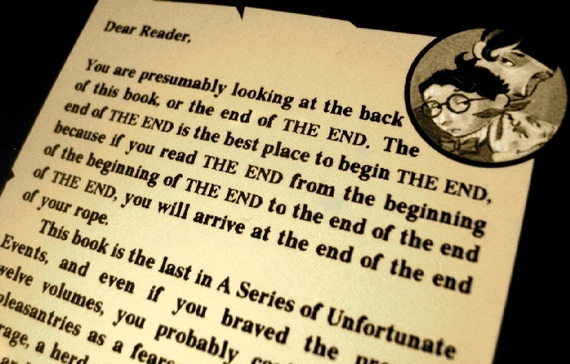

And yet it was the books’ style, not content, I found most compelling of all. Each installment in the series would begin with some iteration of tortured narrator Lemony Snicket (who I didn’t know was actually author Daniel Handler) urging the reader to put the book down and find some happier way to spend his or her time. Snicket would refer to himself extensively, implying that he existed in the same universe as the Baudelaire children. He would repeatedly interrupt the narrative to rant, tell a story, or relay advice, creating a splintered reading experience. Not only would Snicket use ponderous terms like in loco parentis, but he’d also often spend several sentences defining them. And the endings were, as promised, irredeemably depressing. I remained a devoted follower until the final book, The End, was released in 2006, but it wasn’t until several years later that I realized how the series transcended its popular children’s book context: Unfortunate Events was my first introduction to postmodern literature. The loosely defined postmodern literature “movement” (for lack of a better word) started after World War II and adopted many elements from its modernist forbears: a heightened focus on formal experimentation, non-linear narratives, irony, stream-of-consciousness, and a sense of alienation and fractured identity. Postmodernism takes these elements a step further, but incorporates more humor, references to pop culture, and even greater self-consciousness about writing. Some writers of importance: John Barth, Thomas Pynchon, Jorge Luis Borges, William Gaddis, Haruki Murakami, Zadie Smith, and David Foster Wallace. In college, I encountered postmodern novels including Italo Calvino’s If on a winter’s night a traveler…, Don DeLillo’s White Noise, and Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49. My professors presented them as works that were radical, at least in their day. But to me the tone and techniques they deployed felt familiar and somehow comforting. For an example of postmodern hallmarks—such as metafiction, the unreliable narrator, irony, black humor, self-reference, maximalism, and paranoia—look no further than this excerpt from the sixth Unfortunate Events book, The Ersatz Elevator. The word 'bubble' is in the dictionary, as is the word 'peacock,' the word 'vacation,' and the words 'the,' 'author's,' 'execution,' 'has,' 'been,' 'cancelled,' which make up a sentence that is always pleasant to hear. So, if you were to read the dictionary, rather than this book, you could skip the parts about 'nervous' and 'anxious' and read about things that wouldn't keep you up all night, weeping and tearing your hair out. But this book is not a dictionary, and if you were to skip the parts about 'nervous' and 'anxious' you would be skipping the most pleasant parts of the entire story. Nowhere in this book will you find the words 'bubble,' 'peacock,' 'vacation,' or, unfortunately for me, anything about an execution being cancelled. The series also relies heavily on intertextuality, or the way the meaning of a text is shaped by other texts. A brief catalog of texts referenced in the books includes T.S. Eliot’s The Waste Land, Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy, J.D. Salinger’s “For Esme, With Love and Squalor,” and Herman Melville’s Moby Dick. Handler also constructed an elaborate, if purposely obscure, universe around the series, involving a secret organization known by the initials V.F.D. and a cast of shadowy members somehow involved in the death of the Baudelaire parents. With playful pedantry, Handler teased this invented world through allusions in the novels and fictional apocrypha such as the so-called Snicket file. The companion work Lemony Snicket: The Unauthorized Autobiography (it was authorized and not an autobiography) fleshed out the backstory with a bizarre collection of photographs, letters, transcripts, and other mysterious documents. Postmodernism’s influence can be found widely throughout children’s literature, particularly in picture books such as The Monster At the End of This Book or the 1991 Caldecott Medal-winning Black and White. Unfortunate Events merely exaggerated and broadened that trend to lengthier chapter books.

Why might postmodern literary techniques resonate with young readers? One explanation: By complicating the relationship between author and reader, narrator and character, these methods muddy the boundary between text and reality. Young readers might feel the distinction between fact and fiction slipping away, lost in the series’ story-within-a-story-within-a-story. Early in the series’ run, I found myself believing the Baudelaire children or V.F.D. might actually be real (a little more seriously than I believed I’d receive an admission letter from Hogwarts on my 11th birthday). Such was the intoxicating effect of this imaginary world and story that seemed to bleed from beyond the pages.

Of all the series’ postmodern gimmicks, the most endearing was perhaps how Unfortunate Events, in true metafictional fashion, championed the act of reading books as an inalienable good. For all the morally black and gray villains the Baudelaires and readers are forced to endure, the books regularly equated literacy with virtue (“Well-read people are less likely to be evil,” Snicket notes). Though the series’ earliest readers have now mostly grown up, the books will continue to offer a wellspring of sound advice: “When trouble strikes, head to the library. You will either be able to solve the problem, or simply have something to read as the world crashes down around you.” http://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2014/10/postmodernism-for-kids/381739/?single_page=true Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2021

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed