|

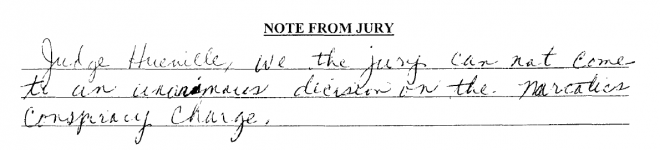

BY DAVID KRAVETS03.04.13 6:29 PM The alleged drug dealer at the center of the Supreme Court’s landmark GPS tracking case had a mistrial declared Monday in his retrial after District of Columbia jurors said they were hopelessly deadlocked. The retrial concerned Antoine Jones, the previously convicted drug dealer whose conviction and life sentence was reversed by the Supreme Court in 2012 after the justices concluded the placement of a GPS tracker on his vehicle was an illegal search. Until the Supreme Court ruled in Jones’ case, the lower courts were mixed on whether the police could secretly affix a GPS device on a suspect’s car without a warrant. After the decision, federal authorities pulled the plug on some 3,000 GPS tracking devices. And in the retrial of Jones — in which he acted as his own attorney — the authorities were barred from using a month’s worth of GPS data that linked him to where the authorities said they found cash and cocaine. The mistrial perhaps underscores that GPS records are a more valuable crime-fighting tool than cell-site data, and bolsters at least one of the government’s arguments that no probable-cause warrants for cell-site data are needed. Federal prosecutors introduced cell-site data obtained without a warrant in the retrial. That evidence was allowed in by U.S. District Judge Ellen Segal Huvelle of the District of Columbia in December. The admittance of the evidence was seen a victory at the time for prosecutors who are shifting their focus to warrantless cell-tower locational tracking of suspects in the wake of the Supreme Court’s ruling. To be sure, the lower courts are still divided about whether a probable-cause warrant is required to obtain cell-site data. “Judge Huvelle, we the jury can not come to an unanimous decision on the narcotics conspiracy charge,” the jury wrote in a note to the judge. The Blog of Legal Times said the jury was deadlocked 6-6 and that prosecutors were mulling a retrial. The cell-site data chronicled Jones’ whereabouts when he made and received about four months’ worth of mobile phone calls in 2005. The records show each call the defendant made or received, the date and time of calls, the telephone numbers involved, the cell tower to which the phone users connected at the beginning and/or end of the call, and the duration of the call. But the data is not nearly as accurate as GPS data, which can virtually pinpoint a person’s location compared to cell-site data. Cell-site data highlights the location of towers where a cell signal pinged. The authorities only had to show that such information was “relevant” to an investigation to get a judge to authorize Cingular to turn over the cell-site data. No probable cause was needed. The cell-site data was not introduced in Jones’ previous trial because the authorities used the more reliable GPS tracking data instead. The government maintained Americans have no expectation of privacy of such cell-site records because they are in the possession of a third party (.pdf) — the mobile phone companies. What’s more, the authorities in arguing for the evidence to be admitted said that the cell site data is not as precise as GPS tracking, and that “there is no trespass or physical intrusion on a customer’s cellphone when the government obtains historical cell-site records from a provider.” Before the Supreme Court, Justice Antonin Scalia’s majority opinion, which was joined by Chief Justice John Roberts, and Justices Anthony Kennedy, Clarence Thomas and Sonia Sotomayor, said the physical act of placing the GPS device on underneath Jones’ car amounted to the unlawful search. (.pdf) http://www.wired.com/threatlevel/2013/03/gps-drug-dealer-retrial/

Comments are closed.

|

Archives

March 2021

|

||||||||||||||

RSS Feed

RSS Feed